For years there has been an interest by many historians in the location of the school operated by Donald Robertson in Drysdale Parrish in upper King and Queen County, Virginia during the last half of the 18th Century. It was a prestigious school attended by children who would become prominent leaders during and after the American Revolution. The location was known to be near Newtown, Virginia and historical records report that the building was frame over a brick foundation. Popular local history indicated that portions of a school building remained standing in the early 20th Century. However, prior to May of 2011, no archaeological investigation had been undertaken.

Donald Robertson – His Life and School

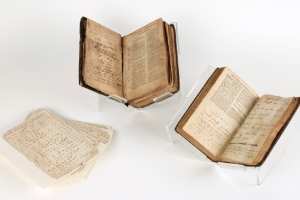

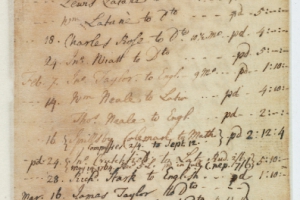

We know much of Robertson’s life because of family letters and comments by President James Madison and by David Mays in his ’52 Pulitzer Prize biography of Edmund Pendleton, but mostly from Robertson’s journal. His small record book contains a powerful record of Robertson’s life at his school from 1758 to 1773. It can now be found at the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond. The personal inscription is difficult to read but tells the historic 15-year account of his life at the school.

In 1752, when he was 35 years old, Donald Robertson, the younger of the two sons of Charles Robertson, a wealthy gentleman of good breeding and character, left Scotland for Virginia. He ventured to the colonies to seek his fortune, and to freely teach his beliefs in independent thought. He was a graduate of the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Because of civil unrest in his country, which scattered the people to the four winds, he came to America to live. There was a demand for qualified teachers in the new world and Robertson quickly gained a notable reputation as a private tutor in the home of John Baylor of Caroline County and Walkerton, Virginia, in King and Queen County.

After five years of tutoring the Baylor children and their neighbors, Robertson was encouraged to open a school on his 150-acre farm in the upper part of King and Queen County. Many influential families that lived in the vicinity wanted their children to enjoy the advantages of a higher education. There were very few secondary teachers in colonial times and Robertson could see that there was a great need for a secondary school. If a planter had a child who was very studious and if he could afford it, he would send him back to England for an education. Other than home schooling, there were no other educational alternatives in the area until the Robertson School.

During the fifteen years from 1758 to 1773, this prestigious school had as many as thirty or forty pupils each year and provided a broad curriculum, in both English and Latin. The school greatly influenced the education of some 200 male and a few female children of the Virginia Colony. Studies included English grammar, composition, and literature, the classical histories of Greece, Rome and England, including authors such as Virgil, Cicero, Horace, and Ovid. French and Latin grammar lessons were offered as well as physics, theology, chemistry, and philosophy. Representative of the many books studied were Montaigne’s Essays, Locke’s Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Addison’s The Spectator, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Montesquieu’s Spirit of Laws, and Ruddiman’s Rudiments of the Latin Tongue.

Robertson is known to have been one of the best school masters within the American British Colonies whose personal discipline and exacting manner set a great example for his numerous pupils, many of whom became leaders of the newly formed United States. Robert and Lawrence Brooke, respectively, became the Governor of Virginia in 1794 and a surgeon who served with John Paul Jones in the Continental Navy during the Revolution. John Penn, a lawyer from Caroline County, moved from Virginia to North Carolina, represented North Carolina in the Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence. Harry Innes entered the Law Office of Edmund Pendleton, a well known political leader throughout the Revolution. His brother James Innes was captain of a militia unit before the Revolution, a colonel during that war, Attorney General of Virginia after the War, and later an eloquent lawyer with a brilliant career. A John Tyler, born in 1747, is believed to have been the John Tyler who was Governor of Virginia and the father of the nation’s tenth president. George Rogers Clark explored the Northwest at President Thomas Jefferson’s direction. There were seven Taylors, brothers and cousins, of whom John Taylor of Caroline, who succeeded Richard Henry Lee as a United States Senator, was the most distinguished. Donald Robertson’s most well known pupil was James Madison, the fourth president of the United States and “Father of the Constitution”. It is believed that the influence of Donald Robertson on James Madison in his formative years was significantly responsible for his writing ability in the Federal Constitution and his work with Thomas Jefferson. Madison’s opinion of his early teacher is revealed in one of his notes written when he was in his early eighties near the close of his life, saying: “All that I have been in life I owe largely to that man.”

The extensive documentation in his personal account and letters does not reveal any record of Robertson’s service in the Virginia Militia. However, he was very supportive of the Revolutionary War and provided the army with corn and beef. On hearing about the signing of the peace treaty in 1781 between Great Britain and the colonies, Robertson is reported to have remarked that the “principles he taught and fought for so hard had finally seen fruition, and he could now rest at ease.” In January, 1783, Robertson died peacefully in his sleep at home in King and Queen County the night after the postal courier had visited to tell him that the Revolutionary War had ended.

The Archaeological Investigation

In the 1930’s George Minor who lived at Owenton, Virginia remembered seeing a building in a field near Newtown, Virginia with ruined thick brick walls and an area of depression whose surrounding ground was scattered with colonial artifacts. Approximately eighty years later in 2010, Philip Minor uncovered some bricks with unusual colors while farming at the same location. This prompted Marian Minor, a King and Queen native, to finally seek the truth about whether this ground surface could have been the location of Donald Robertson’s School. She approached the current owners who gave permission for the site to be historically investigated. Marian Minor and six members of the King and Queen Historical Society sought the help of David Hazzard, archaeologist of the Virginia Department of Historic Resources (VDHR), to perform a small-scale investigation to determine if a more extensive dig should be conducted. During this phase of the project, several pieces of 18th Century glass and brick fragments were found and a decision was made to investigate further. It was indeed possible that this field could be the location of the prestigious school of Donald Robertson that history records as existing from 1758 to 1773.

The dig was conducted by the James River Institute for Archaeology, Inc. (JRIA) in October 2011 with archaeologists Nicholas Luccketti and Anthony W. Smith, and members of the King and Queen Historical Society. The site of the dig was in an agricultural field off Spring Cottage Road near Newtown thought to be where Robertson’s home and school were located on a rise of ground that gradually slopes to the river. For the past 150 years, it has been locally known as “Robertson’s Pocket,” a neck in the bend of the Mattaponi River on the northern side, about four miles above Dunkirk. In the colonial era, Dunkirk was an active river crossing and shipping point for export of tobacco and import of commodities needed by the colonists.

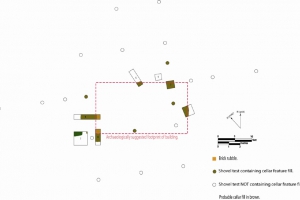

The archaeological investigation located four sides of a colonial period cellar with artifacts that date back to the 18th Century. However, the cellar had been filled in around 1800 and it was difficult to prove that it actually was a school building. Some of the artifacts found included pearl ware, American blue and gray stoneware, green wine bottle glass, brick fragments, nails and iron pieces.

According to the report written by JRIA, Inc, “regardless of what kind of building is represented by the cellar, it is a major feature that must be in the core of the site”. The next logical step is a more intensive investigation, possibly a sonar search of the whole site to identify other major features such as buildings, refuse pits and the extent or borders of the site. In other words, there should be a further investigation to identify other buildings, perhaps a house or large structure that might be the school building.

Locating the site and artifacts of this historical school will encourage and support the identification and protection of King and Queen County’s archaeological resources that can be used for educational and cultural benefits.

Much more information about Donald Robertson and his school can be found in the King and Queen Historical Society Bulletins #14, # 44, and #106.